Spring 2023 - Vol. 18, No. 1

SCIENTIFIC REPORT

Trauma-Informed Care

Perspectives from a Rape Crisis Center

Vogel Leffler

Autumn Vogel, MD

Family Physician, Family Medicine Residency Program

Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health

Brittany Leffler, MSW, LSW

Primary Therapist, Sun Point Wellness Center

Estimates suggest that between 50% and 60% of adults will experience trauma during their lives, with the incidence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the range of 6% to 7%. For adolescents, as many as 5% (including 8% of female adolescents) suffer from PTSD.

1 Exposure to adverse childhood events (ACEs) is associated with an increased risk for long-term complications, perhaps because it is reflected in the cellular makeup — it is associated with an increased risk for DNA methylation and decreased telomere length.

2

The degree of PTSD can be judged using the Sheehan Disability Scale, a brief, validated, proprietary model that helps elucidate impact on a patient’s life.

1,3 Trauma-informed interventions vary and include outpatient therapy, along with eye movement desensitization and reprocessing. Additionally, cognitive behavioral therapy consistently improves symptoms and associated syndromes, such as depression, anxiety, emotional dysregulation, interpersonal problems, and risk-taking behaviors.

4

WHAT IS TRAUMA-INFORMED CARE?

Trauma-informed care is an approach to care delivery that assumes patients have experienced a traumatic event. It encompasses approaches to care delivery that are responsive to a trauma history. Trauma-informed care models are defined by multiple institutions and involve a variety of foundational principles and techniques.

Trauma-informed care assumes individuals under care have experienced trauma simply because data suggest most people have experienced some form of trauma. The ACE study, conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in conjunction with the Kaiser Foundation, showed that as many as two-thirds of U.S. adults carry a history of at least one adverse childhood event.

5 These initially included adverse events of physical, mental, or sexual abuse; physical or emotional neglect; and household dysfunction, including family members with mental illness, incarceration, substance use, or divorce.

5

This study further found links between ACEs and multiple poor medical and social outcomes later in life. These events were cumulative, meaning that the more ACEs one had experienced, the higher the risk for these same mental and physical outcomes. Shockingly, the study revealed that having had four or more ACEs made one twice as likely to smoke, 12 times more likely to have attempted suicide, seven times more likely to be an alcoholic, and 10 times more likely to abuse street drugs.

5

For perspective, CDC data demonstrate that one in six adults reports experiencing four or more ACEs. This is not to mention the one in four biologically female persons who has been raped or the 43% who have experienced sexual violence other than rape.

6 Thus, it is vital to develop professional practices that account for and anticipate these experiences in patients.

KEY PRINCIPLES AND CONSIDERATIONS

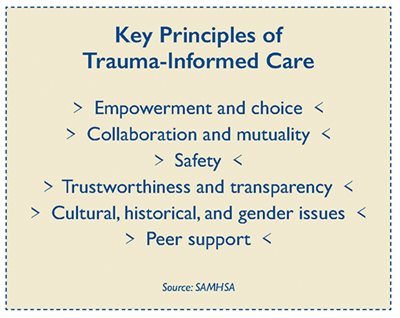

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) defines the key principles of trauma-informed care as:

7

- Empowerment and Choice: This principle highlights the importance of using an individual’s strength to empower them in the development of their own treatment. In other words, shared decision-making.

- Collaboration and Mutuality: This principle represents the importance of maximizing collaboration among the staff, the patient, and within families. Both aspects of this principle highlight the value and importance of sharing power.

- Safety: This principle means developing health care settings and activities that ensure patients’ physical and emotional safety.

- Trustworthiness and Transparency: This principle suggests we create clear expectations about what proposed treatments will entail and how services will be provided, and follow through on plans and expectations with integrity.

- Cultural, Historical, and Gender Issues: This principle asks that organizations develop practices of being responsive to the racial, cultural, and social needs of the individuals being served. If these are not recognized and tended to, the institution risks the possibility of retraumatizing whole populations of patients.

- Peer Support: This principle ensures that survivors are connecting through networks, offering mutual support that entails self-help and promotes recovery.

SAMHSA further outlines guidance to organizations that trauma-informed care be provided through these four Rs:

7

- Realize the impact of trauma and seek to understand pathways to recovery.

- Recognize the signs and symptoms of trauma in patients and staff alike.

- Respond by integrating knowledge of trauma.

- Resist retraumatization by recognizing and changing stressful or toxic institutional practices that could retrigger painful experiences.

The Sanctuary Model of trauma-informed care is a framework to treatment planning, community conversations, and collaborative decision-making that helps people heal from their trauma.

8 The model is SELF:

Safety, Emotion management, Loss, and Future, suggesting providers first recognize that safety was compromised, then understand how emotion management is difficult when safety is compromised. It becomes important to acknowledge what has been lost in this traumatic process and then ultimately turn to the future by focusing on the control we do have over our future outlook, our boundaries, and our choices.

A good example is that of the COVID-19 pandemic. As we faced the uncertainty and assault to our safety, emotions across our society became difficult to manage. Health care workers cried in hallways, people engaged in fist fights over mask-wearing in grocery stores. We lost many loved ones, we lost our ability to travel freely, children lost their ability to attend school in person, we lost our sense of societal stability. As we heal from this collective trauma, we all have had to sort out what we can still control, and ways we can amend our lives to find a sense of peace and stability as we move forward and heal.

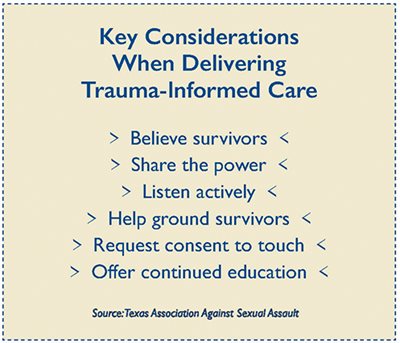

Six main considerations have been proposed when delivering trauma-informed care: believe survivors, share the power, listen actively, help ground survivors, request consent to touch, and offer continued education.

9

Believe Survivors

So often survivors are not believed, which means accepting their story as true is a crucial step in creating a safe space for them. The process of disclosing trauma can appear in many ways. We must understand that experiencing a traumatic event like sexual assault can affect a person’s short-term memory, and often details of such an experience come back to the survivor in a piecemeal fashion.

This has historically led legal officials and medical professionals, who did not understand the experience of the survivor, to question the legitimacy of the survivor’s story. If we start from a place where survivors are believed, we begin to create the kind of safe space where the survivor can feel comfortable to process and heal from their experience.

Share the Power

When working with patients who may have experienced trauma, we must be mindful of our position of power as providers and intentionally choose to share that power in the clinical space. One crucial way to share power in the clinical space is to shift our clinical perspective from “What is wrong with this patient?” to “What happened to this patient?” This includes recognizing the survivor experience; assuring the patient that no matter what occurred before, during, or after the traumatic experience, none of this is their fault; and practicing active, shared decision-making.

Listen Actively

Active listening is an important way to share power and create a safe space for a patient who has endured trauma. It also signals that you are present and available for patients to share their story. Some tips for active listening in the trauma-informed setting include:

- Position yourself at the same physical level as the patient.

- Maintain good eye contact.

- Use verbal and physical cues to signal you are listening, e.g., nodding, eye contact, small affirmative words.

- Never interrupt someone when they are sharing their story.

If you find it difficult to maintain eye contact or listen actively to these patients, it is worthwhile to self-reflect: What is making you uncomfortable and why? Traumatic experiences can be triggering for all parties involved. Do the work to investigate your own feelings as an ongoing reflective process. Doing so will make you a better listener, help you grow as a human and clinician, and allow you to demonstrate to the patient that you are available to support them.

Help Ground Survivors

Often when patients are discussing their trauma, they can find themselves flooded with emotions. It is important for clinicians to be able to help patients ground themselves in the present moment, as the heightened emotions may signify that they are reliving their trauma experience. Here are a few ways to help ground survivors who may be having this experience:

- Ask them to pause and take a few slow deep breaths.

- Ask them to plant their feet on the floor with their back straightened.

- Have them look around the room and name a few of the items that they see.

Many times, having the patient keep their eyes open can help them reorient to the present, which helps pull them out of reliving their trauma.

Request Consent to Touch

Consent is primary in trauma-informed care. It is extremely important to respect the survivor’s personal space. No one has permission to touch any other person without consent. This is especially true for health care workers providing trauma-informed care. Even if you think they want to be touched in a comforting or reassuring manner, never touch a patient until you have obtained permission.

Offer Continued Education

Lastly, it is important for trauma-informed providers and institutions to continually seek education about improving their trauma-informed care. As the adverse childhood events study has expanded, the medical community has learned more about the many ways that childhood events affect health. As a result, our practices must evolve to reflect current understanding of the impact and effects of trauma. The trauma-informed provider will commit to lifelong engagement in continued understanding of these experiences and how best to respond to them.

RESOURCES FOR PATIENTS

Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health providers are fortunate to have YWCA Lancaster’s Sexual Assault Prevention and Counseling Center (SAPCC) as a resource for patients who are survivors of sexual assault. SAPCC is available for people of all races, genders, ages, and ethnicities who have in any way been impacted by sexual assault, abuse, or harassment. Their mission is to support and advocate for survivors and the social circles of survivors. All services are free.

The center provides counseling services, support groups, medical advocacy services, and legal accompaniment to anyone affected by sexual assault, harassment, or abuse, plus they provide training to organizations and primary prevention services. The center has staff members available 24 hours a day, seven days a week for survivors in our community. The 24-hour crisis line is 717-392-7273. Put this number in your phone now, while reading this article. You never know who will need it and when.

REFERENCES

1. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). National Institute of Mental Health. Accessed September 29, 2022.

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/post-traumatic-stress-disorder-ptsd

2. Soares S, Rocha V, Kelly-Irving M, Stringhini S, Fraga S. Adverse childhood events and health biomarkers: a systematic review.

Front Public Health. 2021;9:649825.

3. Sheehan KH, Sheehan DV. Assessing treatment effects in clinical trials with the discan metric of the Sheehan Disability Scale.

Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(2):70-83.

4. Han HR, Miller HN, Nkimbeng M, et al. Trauma informed interventions: a systematic review.

PLoS One. 2021;16(6):e0252747.

5. About the CDC-Kaiser ACE Study. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated April 6, 2021. Accessed September 29, 2022.

https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/about.html

6. Victims of Sexual Violence: Statistics. RAINN. Accessed September 29, 2022.

https://www.rainn.org/statistics/victims-sexual-violence

7. SAMHSA’s Trauma and Justice Strategic Initiative. SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. July 2014. Accessed September 29, 2022.

https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/sma14-4884.pdf

8. Sanctuary Model. Sanctuary Institute. Accessed September 29, 2022.

https://www.thesanctuaryinstitute.org/about-us/the-sanctuary-model/

9. Texas Association Against Sexual Assault. Sexual assault advocate training manual. Updated November 2019. Accessed September 29, 2022.

https://evawintl.org/wp-content/uploads/2016-Sexual-Assault-Advocate-Training-Manual.pdf

Editor’s note: This article is based in large part on a Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health Family Medicine Grand Rounds Presentation given March 15, 2022, by Brittany Leffler. Aside from those already noted above, citations for that talk include the following:

> Bloom SL, Farragher B.

Restoring Sanctuary: A New Operating System for Trauma-Informed Systems of Care. Oxford University Press; 2013.

> Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study.

Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245-258.

> PACEsConnection. 3 Realms of ACEs. 2022. Accessed September 29, 2022.

https://www.pacesconnection.com/pages/3RealmsACEs