Fall 2025 - Vol. 20, No. 3

MEDICAL HISTORY

General Medical Practice in America

A Brief History

Nikitas J. Zervanos, MD

Director Emeritus, Department of Family and Community Medicine

Director Emeritus, Family Medicine Residency Program, 1969-2002

Lancaster General Hospital

Editor’s note: In this issue of JLGH,

we kick off a series of articles by Dr. Zervanos on the circumstances, institutions, and people who built the medical community now recognized as Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health. Much of the information comes from manuscripts he authored and donated to the American Association of Family Physicians Foundation. This first installment offers a brief history of general medical practice in the United States.

European migrants relied on Native Americans and their knowledge of the medicinal value of certain plants to manage their various ailments.

1 Eventually, many different practitioners, who could provide some level of health care, migrated to the colonies, but there were few physicians among them. This was because it took 14 years of education for an English or French physician to attain a medical degree. Thus, it would have required an adventurous spirit and strong economic or political incentives for physicians to migrate and accompany the early settlers to America.

2

It was not until the end of the 17th century that American settlements would have significant numbers of health care practitioners. Besides the relatively few educated physicians from European universities, there were barber-surgeons, apothecaries, midwives, folk practitioners, and minister-physicians, as well as a growing number of apprentice-trained practitioners with knowledge of surgery and compounding pharmaceuticals.

1 The educated physicians and their apprentices were referred to as the “regulars.” By the mid-18th century, of the estimated 3,500 to 4,000 regular physicians, fewer than 400 had received formal medical training, and even then, not all held medical degrees; the vast majority were apprentices.

3

In 1765, Drs. John Morgan and William Shippen, Jr. founded the first medical school in America at the College of Philadelphia, now known as the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

4

Dr. John Morgan (left) and Dr. William Shippen, Jr. (right) founded America’s first medical school in Philadelphia. Morgan portrait by Angelica Kauffman (1741-1807); Shippen portrait by Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827).

Dr. John Morgan (left) and Dr. William Shippen, Jr. (right) founded America’s first medical school in Philadelphia. Morgan portrait by Angelica Kauffman (1741-1807); Shippen portrait by Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827).

The Library and Surgeon’s Hall — part of the medical school at the College of Philadelphia — was used for lectures between 1765 and 1801.

The Library and Surgeon’s Hall — part of the medical school at the College of Philadelphia — was used for lectures between 1765 and 1801.

Early schools also included Columbia in New York and Harvard in Massachusetts; these were influenced by the European medical school model, particularly that of the University of Edinburgh.

Although many of the medical practitioners were apprentice trained and met the standards of the time, the demand for medical professionals exceeded the ability of these early schools to graduate clinicians. Medical education could be a lucrative enterprise, so with few regulations and no real standards, enterprising physicians with rhetorical skills and sufficient backing could establish their own medical schools.

The entrance requirements to most schools were minimal. Not every student was expected to be able to read and write, nor to have a “normal school” education. Most importantly, they needed to be able to pay the fees and agree to attend the lectures. To acquire clinical experience, students were also expected to apprentice with a physician.

5

Respected members of the profession advocated for improved academic standards and for state governments to enforce strict licensing requirements, but these efforts met with little success, as these physicians were considered elitists who were self-serving and feared competition. In 1847, the American Medical Association (AMA) was formed to bring about needed reforms.

Unfortunately, hundreds of schools had already been established with varying degrees of attention to the quality of education being offered, producing physicians with varying degrees of quality and skill. What ultimately defined a “good doctor” may have depended as much on the internal drive of the student as it did on the school from which they had graduated.

3 Many of the physicians graduating from proprietary schools were no better than less formally trained practitioners who simply claimed they were doctors.

During the Jacksonian era (approximately 1820-1840), the sentiment included a distrust of elitists, and whatever regulations or licensing requirements may have been in place were dispensed with or allowed to lapse, such that egalitarianism prevailed and quackery medicine went ungoverned. Among the “irregular” schools of thought that burgeoned at the time were:

- The Thomsonians, inspired by Samuel Thomson (1769-1843), who relied on herbs along with heat, ritual baths, emetics, purgatives, and diuretics.

- The Homeopaths, acolytes of the German physician Samuel Hahnemann (1755-1843), who relied on pharmaceuticals made of highly diluted solutions and powders that often produced effects — when used at full strength — similar to the diseases they were intended to cure.

- The Eclectics, who relied on botanicals, mineral remedies, or a combination of Allopathic, Thomsonian, and Homeopathic practices, or whatever was thought to work.1

Although practitioners, both regulars and irregulars, were expected to conduct themselves ethically, they often made matters worse, for example, by using drugs containing arsenic or mercury, or by employing procedures such as bleeding and cupping.

3

Much can be said of the many respected members of the profession who advocated for improved academic and professional standards. Among them were Drs. Samuel Humes and John Light Atlee of Lancaster, who founded the Lancaster City and County Medical Society in 1844, and Dr. Nathan S. Davis, who in 1847 played a leading role in the development of the AMA. These men advocated for the much-needed reforms in medical education and insisted that state governments enforce strict licensing requirements. Dr. Davis became the AMA’s first president, and Dr. Atlee assumed that role in 1883.

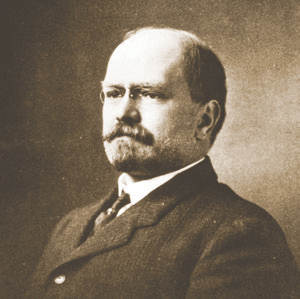

Dr. John Light Atlee co-founded the Lancaster City and County Medical Society and was president of the AMA from 1883-1884. Cabinet card by B. Frank Saylor (d. 1920).

Dr. John Light Atlee co-founded the Lancaster City and County Medical Society and was president of the AMA from 1883-1884. Cabinet card by B. Frank Saylor (d. 1920).

It wasn’t until the post-Civil War era that thousands of Americans chose to acquire their medical education in the great medical centers of Europe. Many of these newly minted medical scientists returned to the United States, entered the academic medical community, and gained the public’s respect and support for major medical education reforms. By 1876, schools that aspired to meet these burgeoning standards joined together to form the Association of American Medical Colleges.

6

In 1893, a new medical school became fully integrated with the newly established Johns Hopkins University. The medical school was to be governed by the university and abide by its high academic standards. Students were required to have earned an undergraduate degree with pre-medical preparation in biology and chemistry, and to undergo a four-year medical school curriculum that included the basic sciences, laboratory research, and clinical experiences, along with bedside teaching and supervision.

1

In 1904, Lancaster-born John Herr Musser, MD (1856-1912), a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, became president of the AMA. During his tenure, the Council on Medical Education was established; its members introduced the categorization of medical schools according to a grading system.

Lancaster-born John Herr Musser, MD, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, served as president of the AMA from 1904-1905.

Lancaster-born John Herr Musser, MD, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, served as president of the AMA from 1904-1905.

The AMA had gained sufficient credibility, influence, and authority to institute significant changes and accredit medical schools, and the AMA commissioned Abraham Flexner, PhD, a highly esteemed educator, to visit and critique all 160 medical schools in the United States and Canada.

In 1910, Dr. Flexner published his findings in what came to be known as the “Flexner Report.” Using the AMA’s grading system and the Hopkins school as the ideal model, the medical schools were categorized into four groups.

7 Even the best schools had to make changes, and grants were provided to schools willing and able to do so.

U.S. medical schools had to meet standards to be accredited by the AMA Council of Medical Education. The AMA, which submitted its report to every state licensing board, recommended that those schools unable to meet minimum standards be forced to close. Some chose to merge, and nearly all came under the governance of a university.

8

By 1920, as the Flexner reforms were fully implemented, only 66 schools remained accredited. Dr. Flexner’s reforms also recommended that every medical school graduate complete a one-year internship approved by the AMA, and thus Lancaster General Hospital developed an AMA-approved internship program soon after Flexner’s recommendations.

9 Completion of an internship as well as the passing of a state licensing exam became the new standard for licensure to practice in Pennsylvania.

With the rapid advancements in medical science and technology, many physicians became self-declared specialists and formed specialty societies to benefit from each other’s expertise. Yet, formalized residency training beyond the internship, and subsequent board certification, did not occur until 1916, when ophthalmology became the first specialty to establish a board. By 1940, an additional 16 specialty boards had formed.

10

There was a strong economic incentive to become a specialist, as specialists were able to garner higher fees. Moreover, the rise of the third-party insurance system gained momentum in the 1930s, as it not only covered the cost of hospitalized patients but also paid the fees for services provided by specialists.

11

As the public became more informed, there was an increasing demand for specialized care. The demand, coupled with the added financial incentives, led most medical school graduates to choose specialty training. Consequently, by the 1950s, the general practitioner was fast disappearing, as less than half of the physicians in America were general practitioners and were not being replaced. This meant that many people, especially in rural America, were faced with limited or no access to a physician.

12

With strong leadership from the newly formed American Academy of General Practice (AAGP), in concert with the AMA’s Council on Medical Education, a two-year residency in General Practice was instituted in 1950. Unfortunately, these programs lacked the prestige of a specialty, and in most cases, they were not much more than an additional year of internship, garnering graduates of this system little respect from the academic medical community and attracting few candidates.

In 1961, Kerr White, MD, who coined the term “primary care physician,” and his colleagues, T. Frank Williams, MD, and Bernard G. Greenberg, PhD, published their classic study on the “Ecology of Medical Care,” which described three levels of care, underscoring the principal role of the primary care physician. Their study helped support the argument that the “primary care physician” is central to delivering health care and can manage the vast majority of a patient’s comprehensive care needs.

13 This study gave credence to the argument that more attention should be given to the education of generalists and the development of a primary care specialty.

AAGP leaders continued to define the comprehensive scope of primary care — including what skills are necessary to care for patients from the beginning to the end of life — and advocated for the importance of disease prevention and health maintenance. Reports from the National Commission on Community Health Services (the so-called Folsom Report), the Citizens Commission on Graduate Medical Education (or Millis Report), and the Ad Hoc Committee on Education for Family Practice of the Council on Medical Education (known as the Willard Report), helped many conclude that all graduates from medical school needed specialized training, including the “primary physician.”

14

Government payment systems also helped the U.S. education system expand physician and non-physician medical manpower. By 1969, when nearly all medical school graduates were choosing a specialty, Family Medicine became America’s 20th primary specialty. Lancaster County’s own Edward Kowalewski, MD, of Akron, was president-elect of the American Academy of Family Physicians and played a leading role in the implementation of the specialty. Medical school graduates soon tripled, and new health practitioner roles — including nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and nurse midwives — were developed to help meet the spectacular demand for health care. Currently, the American Board of Medical Specialties recognizes 40 specialties and 89 subspecialties.

15

As of 2015, primary care physicians made up a third of the total workforce, with only 7% being pediatricians and 13% being internists; the remaining 13% were family physicians.

16 By 2024, the percentage of U.S. physicians practicing primary care had continued to drop, to less than a quarter of those who practice medicine.

17 The 2024 U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration State of the Primary Care Workforce report suggests that by 2037 there will be a shortfall of over 87,000 primary care physicians.

18

REFERENCES

1. Duffy J.

The Healers: A History of American Medicine. University of Illinois Press; 1976.

2. Lyons AS, Petrucelli HRJ.

Medicine: An Illustrated History. Harry N. Abrams; 1978.

3. Starr P.

The Social Transformation of American Medicine. Basic Books; 1982.

4. Corner GW.

Two Centuries of Medicine: A History of the School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania. J.B. Lippincott Company; 1965.

5. King LS.

American Medicine Comes of Age, 1840-1920, Essays to Commemorate the Founding of the Journal of the American Medical Association,

July 14, 1883. American Medical Association; 1984.

6. AAMC History. Association of American Medical Colleges. Accessed August 4, 2025.

https://www.aamc.org/who-we-are/aamc-history

7. King L. The Flexner Report of 1910. In

American Medicine Comes of Age, 1840-1920. American Medical Association; 1984, 92.

8. Johnson, V. The historical development of accreditation in medical education.

JAMA. 1962;181(7):136-139.

9. Lancaster General Hospital. Board of Directors minutes, 20th Report, 1912-1913.

10. Stevens R.

American Medicine and the Public Interest: A History of Specialization. University of California Press; 1971.

11. Geyman JP.

The Modern Family Doctor and Changing Medical Practice. Appleton Century Crofts, Educational Division; 1971.

12. Foster GR. The crisis in general practice: a grass-roots reaction.

JAMA. 1964;187(11):797-800.

13. White KL. The Medical School. In

Life and Death and Medicine. W. H. Freeman and Company; 1973, 10.

14. Flexner A.

Medical Education in the United States and Canada: A Report to The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching; 1910.

15. Specialty and Subspecialty Certificates. American Board of Medical Specialties. Accessed June 2, 2025.

https://www.abms.org/member.boards/specialty-subspecialty-certificates/

16. Dulen JE, Ryan KJ, Alpert JS. Where have the generalists gone? They became specialists, then subspecialists.

Am J Med. 2017;130(7):766-768.

17. Hoffer EP. Primary care in the United States: past, present and future.

Am J Med. 2024;137(8):702-705.

18. State of the Primary Care Workforce, 2024. U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration. November 2024. Accessed June 27, 2025.

https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bureau-health-workforce/state-of-the-primary-care-workforce-report-2024.pdf