Winter 2025 - Vol. 20, No. 4

SCIENTIFIC REPORT

Two Cases of Hemolytic Anemia Due to Paravalvular Leak

Successfully Treated with Percutaneous Closure

Foley Landis Biggs

T. Raymond Foley IV, MD, FACC, FSCAI

Interventional and Structural Cardiologist

The Heart Group of Lancaster General Health

Kimberly Landis, MSN, CRNP

Valve Coordinator, Structural Heart

The Heart Group of Lancaster General Health

Ross Biggs, DO, FACC

Section Chief, Non-Invasive Cardiology

The Heart Group of Lancaster General Health

Paravalvular regurgitation (PVR) is the leading cause of hemolytic anemia in patients with prosthetic heart valves.

1 We present two cases of patients who developed hemolytic anemia and associated symptoms due to paravalvular leak (PVL), both of which were successfully treated with transcatheter closure.

CASE 1

History of Presentation

A 70-year-old female is referred to the Cardiology clinic with complaints of shortness of breath, classified as New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class III. She had undergone transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) in 2022 and surgical mitral valve replacement (MVR) in 2023. Over the previous 12 months, she developed macrocytic anemia.

Upon presentation, her hemoglobin is 8.4 g/dL (normal range: 12-16 g/dL) and her mean corpuscular volume (MCV) is 110 fL (normal range: 80-99 fL).

Past Medical History

The patient’s medical history is significant for cirrhosis due to autoimmune hepatitis and primary biliary cirrhosis overlap, for which she is on chronic immunosuppressive therapy. In 2022, she underwent TAVR at another institution, complicated by a right femoral artery pseudoaneurysm requiring surgical repair.

She later presented to Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health with severe mitral regurgitation due to a posterior leaflet flail, leading to surgical MVR at LG Health. She also had some degree of renal failure.

Physical Examination

On examination, her blood pressure is 136/94 mmHg and her pulse is 87 beats per minute. Cardiac auscultation reveals a II/IV decrescendo diastolic murmur at the left lower sternal border. Jugular venous pressure is normal, and her lungs are clear to auscultation bilaterally.

Investigations

Laboratory evaluation reveals a decline in the patient’s estimated glomerular filtration rate from normal values one year earlier to a nadir of 46 mL/min/1.73 m

2 (reference range: >60 mL/min/1.73 m

2). During this same interval, the MCV has increased from 94 fL to 110 fL. Given these findings, a hemolysis panel is performed, yielding the following results:

Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) (129-260 U/L) 939▲

Haptoglobin (44-215 mg/dL) <30▼

Indirect Bilirubin (0.2-0.7 mg/dL) 1.2▲

Reticulocyte Count (0.5%-2.5%) 4.4▲

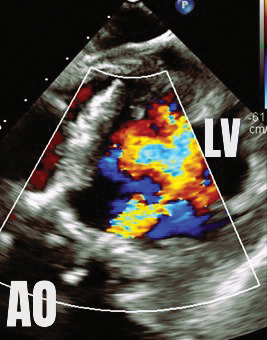

A transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) demonstrates moderate-to-severe paravalvular leak adjacent to the bioprosthetic aortic valve, localized near the left coronary cusp (see Fig. 1).

Left ventricular dimensions and systolic function are preserved (LVEF 55% to 60%), and the mitral valve prosthesis exhibits normal function.

To exclude an infectious etiology, C-reactive protein (CRP) and blood cultures are obtained. The CRP level is within normal limits, and blood cultures show no growth.

Fig. 1. Deep transgastric view of the aortic valve by transesophageal echocardiography demonstrates severe paravalvular leak. In this image, color represents regurgitant flow from the aorta into the left ventricle during diastole.

Management

Fig. 1. Deep transgastric view of the aortic valve by transesophageal echocardiography demonstrates severe paravalvular leak. In this image, color represents regurgitant flow from the aorta into the left ventricle during diastole.

Management

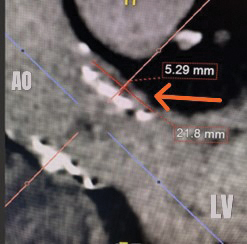

The case is reviewed by a multidisciplinary cardiology team consisting of a structural interventional cardiologist, a cardiothoracic surgeon, and a noninvasive cardiologist with expertise in advanced cardiac imaging. The location and dimensions of the paravalvular leak are deemed suitable for transcatheter closure using a nitinol vascular plug (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Computed tomography angiogram long axis (left) and short axis (right) views of the paravalvular defect below the left main coronary artery. The orange arrows highlight the defects.

Under general anesthesia and with transesophageal echocardiography guidance, the defect is successfully crossed using a hydrophilic guidewire introduced via the right radial artery. A 6-French guide catheter is advanced across the defect, and a 12-mm nitinol vascular plug is deployed. Prior to device release, selective coronary angiography of the left main coronary artery is performed to confirm vessel patency (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Transcatheter paravalvular leak closure. The orange arrow identifies the distal aspect of the vascular plug, positioned below the aortic valve. The white arrow identifies the proximal aspect of the plug, in the left coronary cusp of the aortic root and outside of the prosthetic aortic valve frame. Coronary angiography reveals a patent left main coronary artery.

Fig. 3. Transcatheter paravalvular leak closure. The orange arrow identifies the distal aspect of the vascular plug, positioned below the aortic valve. The white arrow identifies the proximal aspect of the plug, in the left coronary cusp of the aortic root and outside of the prosthetic aortic valve frame. Coronary angiography reveals a patent left main coronary artery.

Post-deployment TEE demonstrates complete elimination of the paravalvular leak.

The patient is discharged the following morning in stable condition. At the six-week follow-up visit, laboratory studies show complete resolution of anemia and renal dysfunction. Her dyspnea had resolved, and she remains asymptomatic one-year post-procedure.

CASE 2

History of Presentation

A 54-year-old woman with a history of rheumatic heart disease who has previously had a surgical aortic and mitral valve replacement presents with fatigue, malaise, and exertional dyspnea, corresponding to NYHA functional class II symptoms.

Past Medical History

At age 46, the patient had undergone surgical mitral valve replacement with a bioprosthetic valve. She subsequently developed severe aortic regurgitation due to valve insufficiency and, at the age of 49, underwent another surgical aortic and mitral valve replacement using mechanical prostheses. Due to the presence of mechanical valves, she is maintained on chronic anticoagulation with warfarin.

Physical Examination

On examination, blood pressure is 123/64 mmHg and heart rate is 75 beats per minute. Cardiac auscultation reveals a grade II/VI holosystolic murmur audible throughout the precordium. Jugular venous pressure is normal, and lung auscultation is clear bilaterally.

Investigations

Transthoracic echocardiogram demonstrates normal prosthetic valve function without evidence of paravalvular leak. Laboratory evaluation is notable for macrocytic anemia (hemoglobin 10.2 g/dL, MCV 101.2 fL). Fecal occult blood testing is negative, and iron studies are within normal limits. Given the laboratory findings, a hemolysis panel is performed, yielding the following results:

Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) (129-260 U/L) 1,009▲

Haptoglobin (44-215 mg/dL) <30▼

Indirect Bilirubin (0.2-0.7 mg/dL) 0.6

Reticulocyte Count (0.5%-2.5%) 4.6▲

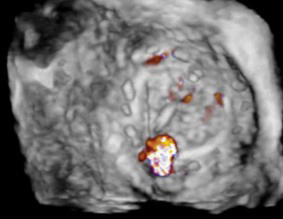

Subsequent TEE reveals a moderate-to-severe paravalvular leak along the posterior aspect of the mechanical mitral valve (see Fig. 4).

The aortic and mitral prostheses are otherwise functioning normally, and left ventricular systolic function was preserved (LVEF 55% to 60%).

To exclude an infectious etiology, CRP and blood cultures are obtained. The CRP level is within normal limits, and blood cultures show no growth.

Fig. 4. Transesophageal echocardiogram demonstrating mitral PVL. Short axis view (top) of the prosthetic mitral valve from the left atrium using three-dimensional (3D) echo. Color doppler at the 6 o’clock position represents regurgitant flow outside of the mitral prosthesis during systole. Long axis view (bottom) of the prosthetic mitral valve demonstrating the same PVL.

Management

Fig. 4. Transesophageal echocardiogram demonstrating mitral PVL. Short axis view (top) of the prosthetic mitral valve from the left atrium using three-dimensional (3D) echo. Color doppler at the 6 o’clock position represents regurgitant flow outside of the mitral prosthesis during systole. Long axis view (bottom) of the prosthetic mitral valve demonstrating the same PVL.

Management

Following a comprehensive evaluation by a multidisciplinary cardiology team, transcatheter PVL closure is recommended. Under general anesthesia, the right femoral vein is accessed. A transseptal puncture is performed using a radiofrequency wire under guidance to gain access to the left atrium.

A steerable sheath is then used to facilitate antegrade crossing of the mitral PVL (see Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Fluoroscopy of PVL closure. Advancing a wire (orange arrow, above left) from the left atrium across the mitral PVL into the left ventricle with the use of a steerable sheath after crossing the interatrial septum. Fully deployed vascular plug (white arrow, above right) within the defect, leading to resolution of PVL.

Fig. 5. Fluoroscopy of PVL closure. Advancing a wire (orange arrow, above left) from the left atrium across the mitral PVL into the left ventricle with the use of a steerable sheath after crossing the interatrial septum. Fully deployed vascular plug (white arrow, above right) within the defect, leading to resolution of PVL.

A stiff guidewire is advanced into the left ventricle, over which a 6-French coronary guide catheter is positioned. A 12-mm nitinol vascular plug is deployed across the defect, ensuring it straddles the PVL (see Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Final short axis view of the mitral valve using 3D echocardiography. The image represents the view from the left atrium. The vascular plug (white arrow), deployed at the 6 o’clock position, now occupies the defect demonstrated in the short axis view of Fig. 4.

Fig. 6. Final short axis view of the mitral valve using 3D echocardiography. The image represents the view from the left atrium. The vascular plug (white arrow), deployed at the 6 o’clock position, now occupies the defect demonstrated in the short axis view of Fig. 4.

The device is then released. Post-deployment TEE demonstrates near-complete resolution of the PVL.

The patient is discharged the following day in stable condition. After six weeks, her anemia has completely resolved, and she remains asymptomatic.

SUMMARY

Paravalvular leak is a relatively common complication following prosthetic cardiac valve implantation, with an incidence ranging from 6% to 15%.

2 Patients may present with heart failure symptoms or hemolytic anemia. Hemolysis often occurs with smaller defects, where high-velocity jets generate shear stress, leading to red blood cell fragmentation.

Paravalvular leak results from incomplete apposition of the prosthetic valve to the native annulus, which can arise from friable annular tissue, dense annular calcification, suture dehiscence, or infection. Historically, surgical intervention has been the standard approach for clinically significant PVL but is associated with variable outcomes and elevated operative risk.

3,4 Percutaneous PVL closure offers a minimally invasive alternative and has been demonstrated to be safe and effective in multiple studies.

5,6

Selection of an appropriate treatment strategy involves careful assessment of defect location, size, and morphology using echocardiography and contrast-enhanced computed tomography. Three-dimensional reconstructions are essential for determining percutaneous closure feasibility.

Very large defects (>⅓ of the annular circumference) or obvious valve dehiscence typically require surgical repair, as do cases associated with active endocarditis, which necessitate debridement. Current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines recommend percutaneous PVL closure for patients with suitable anatomy, symptomatic heart failure, and/or hemolysis, particularly when surgical risk is high.

7

A multidisciplinary “Heart Team” approach is critical for optimal patient selection. At Penn Medicine Lancaster General Hospital, patients with structural heart disease, including PVL, are evaluated by a team composed of a structural interventional cardiologist, a cardiothoracic surgeon, and a noninvasive cardiologist with expertise in cardiac imaging. Consensus recommendations are made after review of all relevant data.

Techniques for percutaneous PVL closure vary by valve location. The cases presented highlight both an antegrade transseptal approach for mitral PVL and a retrograde aortic approach for aortic PVL. Closure devices, available in various shapes and sizes, are typically constructed from nitinol, a nickel-titanium alloy with super elastic properties, allowing conformability within irregular defects.

Procedures are performed under general anesthesia via femoral arterial or venous access. Transesophageal echocardiography and fluoroscopy guide device deployment. Procedures generally take one to two hours, and patients are typically monitored overnight and discharged with minimal restrictions.

CONCLUSION

The presence of hemolytic anemia in a patient with a prosthetic cardiac valve should prompt evaluation for paravalvular regurgitation. Symptomatic PVL is associated with increased morbidity and mortality if left untreated.

8 Percutaneous transcatheter PVL closure is a safe, minimally invasive, and effective treatment option for many patients. Ongoing research and advances in device technology continue to improve procedural outcomes and expand the population of patients who may benefit from this therapy.

REFERENCES

1. Eleid MF, Cabalka AK, Malouf JF, Sanon S, Hagler DJ, Rihal CS. Techniques and outcomes for the treatment of paravalvular leak.

Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8(8):e001945.

2. Hammermeister K, Sethi GK, Henderson WG, Grover FL, Oprian C, Rahimtoola SH. Outcomes 15 years after valve replacement with a mechanical versus a bioprosthetic valve: final report of the Veterans Affairs randomized trial.

J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36(4):1152-1158.

3. Miller DL, Morris JJ, Schaff HV, Mullany CJ, Nishimura RA, Orszulak TA. Reoperation for aortic valve periprosthetic leakage: identification of patients at risk and results of operation.

J Heart Valve Dis. 1995;4(2):160-165.

4. Akins CW, Bitondo JM, Hilgenberg AD, Vlahakes GJ, Madsen JC, MacGillivray TE. Early and late results of the surgical correction of cardiac prosthetic paravalvular leaks.

J Heart Valve Dis. 2005;14(6):792-800.

5. Calvert PA, Northridge DB, Malik IS, et al. Percutaneous device closure of paravalvular leak: combined experience from the United Kingdom and Ireland.

Circulation. 2016;134(13):934-944.

6. Sorajja P, Cabalka AK, Hagler DJ, Rihal CS. Long-term follow-up of percutaneous repair of paravalvular prosthetic regurgitation.

J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(21):2218-2224.

7. Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines.

Circulation. 2014;129(23):2440-2492.

8. Shah S, Alashi A, Pettersson GB, et al. Characteristics and longer-term outcomes of paravalvular leak after aortic and mitral valve surgery.

J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;157(5):1785-1792.e1.