Winter 2025 - Vol. 20, No. 4

PHOTO QUIZ FROM THE PRIMARY CARE ADVANCED PRACTICE PROVIDER ONBOARDING PROGRAM

A Massive Encounter

Elizabeth Ruhl, MSN, CRNP, FNP-C

Nurse Practitioner, Family Medicine Lincoln

Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health Physicians

CASE HISTORY

A 56-year-old male presents with a chief complaint of back pain located between his spine and left shoulder blade. He reports that symptoms began after tripping into a column at a gas station about a month prior to the office visit. He reports his pain is intermittent and can radiate up and down the muscles to the left of his spine.

The patient works in construction with a lot of overhead reaching; he says the pain is especially noticeable at the end of the day after work. The pain can be dull or tight, and he occasionally feels a sharp pain that radiates under his scapula and across the left posterior ribs. He has tried ibuprofen and a heating pad with minimal relief.

His past medical history includes essential hypertension treated with olmesartan-HCTZ™ 40-12.5 mg. No diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, or constipation are noted, and the patient denies difficulty with urination. He does note that he has not had much appetite since the fall of 2024.

The patient also points to a large area of swelling in the left upper quadrant of his abdomen; he states he started experiencing left lower quadrant abdominal pain in October 2024 and was told that he had a mild case of diverticulitis. A colonoscopy was completed at the time and all of the removed polyps were benign. The tenderness in the left lower quadrant has since disappeared, but he noticed the swelling in the left upper quadrant sometime after having the colonoscopy.

He denies other constitutional symptoms, but when his last three weights are reviewed, it appears he has lost more than 30 pounds in the last year; this has been unintentional. His vital signs are stable and he is afebrile. A physical exam of his back reveals no tenderness, bruising, swelling, muscle spasms, bony tenderness, or decreased range of motion. There are no significant findings in the neck, upper extremities, or lower extremities.

The abdominal exam reveals a large, firm, non-tender mass in the left upper quadrant. The mass visibly protrudes when he is supine. There is no skin discoloration, and the edges of the mass are unable to be definitively palpated due to size and location. No other significant findings emerge during the abdominal exam.

The patient agrees to continue heat application and add a muscle relaxer for left back pain.

Considering this left upper quadrant mass in the setting of anorexia and unintentional weight loss, a complete blood count with differential and comprehensive metabolic panel is ordered, along with an abdominal ultrasound.

QUESTIONS

- What are some differential diagnoses for a left upper quadrant mass in this patient?

- What diagnoses may present with findings of anorexia, weight loss, and a painless abdominal mass?

- What initial laboratory testing is most important to consider?

- What is the preferred diagnostic imaging choice for abdominal masses?

ANSWERS

- The differential diagnoses in this case include splenomegaly, hernia, lipoma, gastrointestinal mass, hepatic mass, pancreatic mass, renal mass, and adrenal mass.

- Diagnoses that may present similarly include malignant disease processes, specifically renal, hepatic,1 splenic, pancreatic,2 gastrointestinal, and adrenal3 malignancies.

- Initial lab testing should include a comprehensive metabolic panel and complete blood count with differential. Evaluating hepatic and renal function along with any platelet abnormalities or anemia can help direct the diagnostic process.1,2 Given the wide range of diagnostic possibilities, other laboratory testing might include an evaluation of adrenal hormones such as cortisol, aldosterone, and androgens, as well as a fasting glucose.2

- Preferred imaging for the diagnostic evaluation of abdominal masses varies. If there is a high suspicion for hepatic mass, an abdominal ultrasound can be considered. However, an abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan with and without contrast is generally recommended for both diagnostic and staging evaluation for most of the potential diagnoses in this case.1-3

ADDITIONAL CASE HISTORY

Laboratory results include the following: RBC: 4.46; hemoglobin: 11.8; HCT: 37.8; MCH: 26.5; MCHC: 31.2; AST: 74. All other levels are within normal limits. Upon reviewing results and assessment findings, a CT scan of the abdomen would be appropriate for further evaluation.

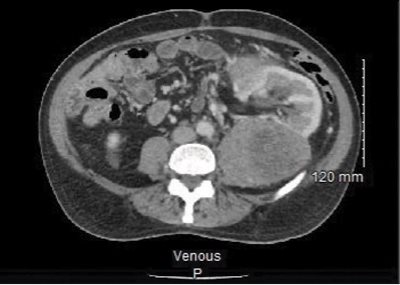

The CT scan impression is as follows: “Huge heterogeneous vascular left-sided retroperitoneal mass displacing adjacent structures and likely renal in origin. Findings most likely represent a renal cell carcinoma.”

The mass is noted to be at least 25 cm in diameter per the radiologist’s interpretation (see Fig. 1), and the left kidney and other local structures are noted to be anteriorly displaced (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 1. CT abdomen with contrast. “Huge” heterogeneous mass of the left abdomen (estimated 25 cm at largest diameter). Left kidney unable to be visualized in this view.

Fig. 1. CT abdomen with contrast. “Huge” heterogeneous mass of the left abdomen (estimated 25 cm at largest diameter). Left kidney unable to be visualized in this view.

Fig. 2. CT abdomen with contrast. Left kidney with anterior displacement due to mass along with other local structures.

The patient is contacted and informed of the results; an urgent referral is placed for the patient to see a urologist.

DISCUSSION

Abdominal masses may go unidentified due to vague symptoms that can be attributable to other disease processes, therefore it is important to conduct a thorough history and abdominal exam for each patient presenting with the symptoms described in this case.

1-3

Prompt laboratory testing — including a comprehensive metabolic function and complete blood count — and imaging are essential in identifying masses, narrowing the differential diagnoses, and ensuring the prompt referral to appropriate specialists for further management. Additionally, while abdominal ultrasound is appropriate for a variety of abdominal disease processes, a CT with and without contrast is the most appropriate initial imaging when evaluating a possible mass.

1-3

Adrenocortical carcinomas (ACC) have an incidence rate of one to two cases per one million adults. ACCs can occur throughout the lifespan but typically are diagnosed in individuals who are over 40 years old. Between 40% and 60% of cases present with signs of hormone excess, the most common constellation being Cushing’s syndrome, with symptoms including hypertension, central weight gain, the development of diabetes mellitus, and easy bruising. Patients may also present with abdominal pain/fullness, weight loss, and anorexia.

4

Although adrenal masses are often found incidentally on studies done for other reasons, the evaluation of a suspected abdominal mass should include a CT of the abdomen/pelvis with and without contrast.

Staging of ACC is approached similarly to other types of malignancies with consideration of where it may have metastasized. Most patients are not diagnosed until stages III and IV, when surgical intervention is not possible and thus the prognosis is poor.

4 The treatment is palliative instead of curative in these cases.

4

There is limited high-quality evidence to support a specific treatment pathway. Patients with less advanced disease (stages I-III) have better five-year survival rates.

4

Currently, the only curative treatment for ACC is complete surgical resection. Combination treatment with etoposide, doxorubicin, cisplatin, and mitotane should be considered for advanced ACC; radiotherapy may be considered on a case-by-case basis.

4,5

Immunotherapy is currently under study for the management of ACC, especially for patients with an otherwise poor prognosis.

5 Several clinical trials and international collaborations remain underway to further study and improve the treatment, quality of life, and outcomes for patients with ACCs.

4 These include the International Pediatric Adrenocortical Tumor Registry through St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, the ADIUVO trial through the University of Turin in Italy which is studying the effectiveness of adjuvant mitotane therapy, and the European Network for the Study of Adrenal Tumours (ENSAT).

CASE OUTCOMES

The patient is seen back in the office of his primary care team about two months after his initial presentation and one month after surgery. Ultimately, he underwent an open resection of the left retroperitoneal mass, a left nephrectomy, a distal partial pancreatectomy, and splenectomy. The final pathology demonstrated a high-grade ACC.

All margins of removed tissues were free of abnormal cells, including one retroperitoneal lymph node. The most effective treatment for ACC is surgical resection, thus no radiation, chemotherapy, or adjuvant medications are necessary.

3

The patient’s recovery has been satisfactory per his surgeons, and serial imaging is planned to monitor his recovery. At the time of his visit with the primary care team, he reports he is doing well and, specifically, that his appetite has returned. His vital signs are stable, and his lab results have returned to normal.

REFERENCES

1. Sudhakar V, Chandan V, Roberts L. Liver masses: a clinical, radiologic, and pathologic perspective.

Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(9):1414-1429.

2. Hidalgo M. Medical progress: pancreatic cancer.

N Engl J Med. 2010;362(17):1605-1617.

3. Rowe N, Kumar R, Scheida N, et al. Diagnosis, management, and follow-up of the incidentally discovered adrenal mass: CUA guideline endorsed by the AUA.

J Urol. 2023;210(4):590-599.

4. Shariq O, McKenzie T. Adrenocortical carcinoma: current state of the art, ongoing controversies, and future directions in diagnosis and treatment.

Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2021;12:20406223211033103.

5. Zhang Z, Liu N, Li Q. EDP-M plus sintilimab in the treatment of adrenocortical carcinoma: a case report.

Transl Cancer Res. 2022;11(6):1829-1835.